HUNTER, CLEMENTINE

HUNTER, CLEMENTINE

(1886–1988)

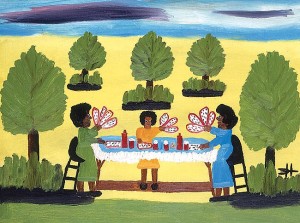

drew upon her experiences living and working as a field hand at the Hidden Hill plantation near Cloutierville, Louisiana, and working as a cook at the MelrosePlantation in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, to produce thousands of paintings that recorded daily plantation life. A mecca for artists, Melrose was an ideal place tostoke Hunter’s desire to “mark a picture.”Born Clementine Reuben in 1886 at the Hidden Hill plantation, this African American artist witnessed in her lifetime the gradual dissolution of the plantation system.The oldest of seven children, she gave birth to seven children, as did her mother, Antoinette Adams. After Hunter’s husband, Charles Dupre, died in 1914, she marriedEmmanuel Hunter, a woodchopper at Melrose, in 1924. Hunter picked cotton and pecans to help provide for her family, and she took in washing and ironing fromMelrose when Emmanuel was diagnosed with cancer in the 1940s. A creative person, she sewed clothing, made dolls, wove baskets, and created functional pieced-cotton quilts for her family in the spare time she could find.Hunter began painting using the discarded paint tubes of the artist Alberta Kinsey, a guest of Cammie Henry’s, the owner of Melrose. Encouraged by the landscapeartist and historian François Mignon, Hunter began to paint people working on the plantation; she also planted cotton; harvested gourds, pecans, and sugarcane; madesyrup; and washed clothes. She portrayed women doing kitchen chores, paring apples, and caring for children. She painted people in lighter moments: dancing, playingcards, and socializing Saturday nights at the local honkytonk. Religion was an important part of Hunter’s life as well as that of the community, so she painted peoplegoing to church and participating in baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Crucifixions and Nativity scenes were also among the subjects she painted. The artist lovedflowers, particularly zinnias, and often painted them displayed in large pots. To encourage her to experiment, her friend, teacher and writer James Register,commissioned Hunter to create a number of abstract works. Register realized, however, that Hunter preferred to follow her own muse and make representationalworks.Using oil paint and gouache, Hunter painted in a flat style, close to the picture plane, or the imaginary window that separates the viewer from the image, using pure, bright colors. Linear layering (the placing of shapes above or on top of other shapes) was substituted for shading and naturalistic perspective. Hunter painted mostly oncardboard, occasionally on canvas, and on other materials as diverse as window shades, lampshades, spittoons, and bottles.This prolific painter produced several thousand paintings, most about twenty by thirty inches in size, but among her masterpieces were also room-size murals.Melrose’s

Africa House Mural,

painted by Hunter, documents the diverse activities of plantation life. Among the mural’s vignettes is a self-portrait of the artist, seatedin a chair and painting in front of an easel. Hunter also created several hand-sewn, appliquéd, and pictorial quilts with scenes of life at Melrose. The different signatureinitials she used during her life aid in dating many of her works.Hunter was motivated enough to make art until the last few months of her life, when she became too ill to continue working. She said, “God gave me the power.Sometimes I try to quit paintin’. I can’t. I can’t.” She also acknowledged that “paintin’ is a lot harder than picking cotton. Cotton’s right there for you to pull off thestalk, but to paint you got to sweat yo’ mind.” She thought of her art as “a gift from the Lord.” Hunter’s achievement went beyond simply providing pleasure for viewers. Her portrayals of Southern plantation life, recorded over more than half a century, are important documents, as important as letters or diaries, from asignificant era in American history.Hunter received a measure of artistic recognition during her lifetime. She was awarded an honorary doctorate from Northwestern University in 1986, and her work is represented in the permanent collections of many American museums and has been seen in exhibitions throughout the United States.

See also

African American Folk Art (Vernacular Art); Painting, American Folk; Quilts; Religious Folk Art

.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gilley, Shelby R.

Painting by Heart: The Life and Art of Clementine Hunter.

Baton Rouge, La., 2000.Kogan, Lee. “Unconventional Eloquence: The Art of Clementine Hunter.”

African American Folklife in Louisiana,

vol. 17 (1993): 17–23.Sellen, Betty-Carol, and Cynthia Johanson.

Twentieth-Century American Folk, Self Taught, and Outsider Art.

New York, 1993.Wilson, James L.

Clementine Hunter.

Gretna, La., 1988