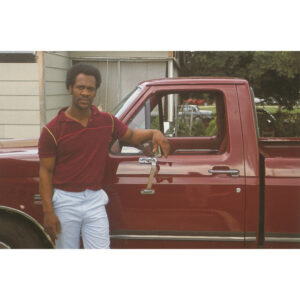

DIAL, RICHARD

DIAL, RICHARD

(1955–)

is an accomplished metalworker and furniture maker who periodically creates austere yet whimsical sculptural chairs. The second son of renowned artist Thornton DialSr. (1928–), he worked as a machinist at the Pullman Standard Company in Bessemer, Alabama, where his father was employed, before leaving to pursue his dreamof owning his own business. In 1984, along with his father and brother, Dan, he founded Dial Metal Patterns, a small business making metal patio furniture, which from beginnings in a tin shed in his father’s backyard developed into a cottage industry through the 1980s and 1990s.Richard Dial christened his original line of functional furniture “Shade Tree Comfort,” and adapted the theme of comfort to his sculptures. They bear names like

TheComfort of Moses and the Ten Commandments, The Comfort of Prayer, The Comfort of the First Born, The Man Who Tried to Comfort Everybody,

and

The Comfort and Service My Daddy Brings to Our Household.

In each work, the physical support the chair provides plays against the psychological comfort (or discomfort) of the piece’s subject. Fabricated with the same basic steel armatures as Dial’s patio furniture, the sculptures are life-size and anthropomorphic, with stylized features and a few scenesetting details, such as wire shoelaces to indicate feet, or runic incisions in wood panels to imply the stone tablets of the Decalogue, or Ten Commandments. The range of emotional tones in the works’ components is often astonishingly complex: the parallel steel bands of the bodiesare ascetic and regular; the faces, round and open; the themes, quietly challenging; the painted surfaces, frenzied and dripped. The result is art as self-effacing as it isexalted. Human figures become both servants (literal seats) and royalty, much like living thrones, with an autobiographical power that transforms any sitter into aRichard Dial, whose investiture is his ancestors, his convictions, his family, and his trade skills.Dial’s metalworking ties him to the history of his region and of black people’s lives there. The mining and industrial corridor of north central Alabama was originallydeveloped at the turn of the twentieth century to offer a low-cost alternative to Northern-made steel; in greater Birmingham, workers were not members of the unions,generally, and often made up of convict labor. In fact, it was the harsh, dangerous conditions in local factories that pushed the Dials to start their own small business.Dial’s art explores the comforts and bonds that members of the black working class forged within a civic environment that denied them economic and political rights.

See also

African American Folk Art (Vernacular Art); Chairs; Thornton Dial Sr.; Sculpture, Folk.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnett, Paul, and William Arnett.

Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South,

vol. 2. Atlanta, Ga., 2001.Rosenak, Chuck, and Jan Rosenak.

Museum of American Folk Art Encydopedia of Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists.

New York, 1990