CUNNINGHAM, EARL

CUNNINGHAM, EARL

(1893–1977)

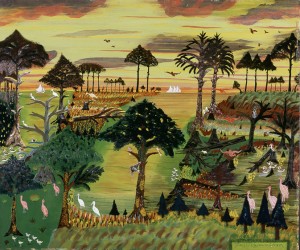

seldom sold his paintings, and his artwork received little significant attention during his lifetime. His posthumous career was launched in 1986 by Robert Bishop (1938– 1991), the late director of New York’s American Folk Art Museum, with an eleven-city museum tour. The collectors Marilyn and Michael Mennello, who acquiredmuch of the artist’s estate, proved pivotal in furthering his reputation, and in 1998 they donated a substantial portion of their holdings to establish the Mennello Museumof American Folk Art in Orlando, Florida. Cunningham’s almost invariable subject is the American coastline, the interplay of snug harbors, open seas, and sailingvessels, recalling a lifetime spent largely on or near the water. Despite the artist’s often-serene subject matter, a sense of subliminal unease is imparted by a palette thatfavors contrasting complementary hues.Born to a relatively poor farming family in Edgecomb, Maine, Cunningham was forced by economic necessity to become an itinerant peddler at the age of thirteen.Eventually he turned to sailing, traveling the East Coast on the large cargo schooners that were a principal means of interstate trade in the era before World War I. Evenafter his marriage to Iva Moses in 1915, Cunningham preferred to roam, first on a houseboat and later in a camper truck. During the 1920s, the couple earned their living scavenging relics and coral in Florida and bringing them north to Maine to sell. Periodically Cunningham would settle down, attempting at one point to farm inMaine and, during World War II, raising chickens for the United States Army. These stabs at stability, however, seem to have been doomed by the artist’s irascibletemperament. He quarreled with his family in Maine, and eventually separated from his wife.By 1949, when Cunningham established an antiques and secondhand shop called the Over-Fork Gallery in St. Augustine, Florida, he had grown distinctly paranoid.Dubbed the “Crusty Dragon of St. George Street,” he became convinced that the local preservation committee was out to burn down his shop, or even murder him.His often erratic behavior notwithstanding, however, Cunningham managed to sustain his business and, during his years in St. Augustine, devoted more and more timeto painting. In the last twenty-eight years of his life, he created approximately 450 paintings based on memory, history, and fantasy, including some of his favoriteimages of early-twentieth-century sailing schooners, scenes of New England villages and harbor towns, and provocative portrayals of Seminole Indian life enhancedwith Viking ships.His artistic career late in life was made possible in part through the generosity of his landlady, Teresa Paffe, who subsidized his rent and dreamed of one daymarrying him. Cunningham nonetheless became increasingly embittered; he died by his own hand at the age of eighty-four.

See also

American Folk Art Museum; Robert Bishop; Mennello; Painting, Memory

.

Bishop, Robert.

Folk Painters of America.

New York, 1979.Hobbs, Robert.

Earl Cunningham: Painting an American Eden.

New York, 1994.Johnson, Jay, and William C.Ketchum Jr.

American Folk Art of the Twentieth Century.

New York, 1983